A rather impressive thunderstorm woke me up early. The rain drops clattered against the window and there were several long rumbles of thunder. I’ve always thought thunder sounded different in Orlando and Chicago. In Orlando, it’s deep and rumbles and rolls for a long time. In Chicago, it’s more of a crack and it dies down quicker. I’ve always thought it had to do with the tall buildings and large body of water reflecting the sound in Chicago. But here, thunder sounds more like it does in Orlando. So perhaps it’s the air temperature that has more of an effect. It was a muggy 85 already at 6:30am.

Fortunately, the forecast predicted the weather would clear up by 9ish, which is when our walking tour with Little Adventures in Hong Kong started. This company offers small private tours (capped at 3 adults) that can be tailored to your interests.

We asked for a mashup of their “Essential Hong Kong” history tour and the street food frenzy, “Won-ton-a-thon.” In my initial communications with them, I tried to emphasize a focus on food over history. The end result turned out to be reversed, but that was just as well (which I’ll explain in a bit).

We took a cab from our hotel to the lobby of The Pottinger hotel where we met our lovely guide, Yvonne. Her life story is incredible. I’m not sure where she was born, but she went to boarding school in London, college in the US, lived in Wisconsin and Philadelphia, lived in East Africa working at a museum, traveled extensively, and settled in Hong Kong about 10 years ago. She studied anthropology, worked at several museums, but also worked as a film editor and a journalist. It was hard to keep track!

She was incredibly knowledgeable about the history and layout of the city. We explored a few areas of the Central district, including Soho (South of Hollywood Street) and the Mid-levels.

Since we hadn’t had anything to eat yet we headed off for food. Along the way, we stopped to admire the menu of a Cantonese restaurant, that wasn’t open yet. We stopped for a couple of reasons. First, history. The sign said they had been proudly serving since 1860. However, Yvonne explained they hadn’t been serving that long in Hong Kong. They were refugees from China.

The history of Hong Kong is punctuated with waves of refugees from China, fleeing from communism in the 50s, and then from Mao and the Cultural Revolution in the late 60s and early 70s.

The second reason we stopped was to hear a funny story about how this restaurant’s signature sauce became known as “Swiss sauce.” An Englishman came into the restaurant and ordered chicken wings in sauce, which he really loved. He asked the waiter what the sauce was called. In an east meets west misunderstanding, he heard “Swiss” though the waiter was trying to communicate that it was a “sweet sauce.” It would have ended there, except the Englishman settled nearby and continued to return to the restaurant ordering the chicken wings in “Swiss sauce.” Eventually, it stuck.

Our first bite on the tour turned out to be more of a gulp. We went to Tsim Chai Kee, a noodle shop. The owner insisted we take a nice booth in the back of the restaurant because it was cooler. She was very friendly and chatted away with Yvonne in rapid-fire Cantonese.

Yvonne ordered us three types: beef brisket, fish balls, and shrimp (or prawn in this part of the world) wontons. The bowls were enormous!

The large portions were the result of a rivalry. This restaurant opened its doors across the street from a famous noodle shop, Mak Noodles (which only opens later in the day). Mak serves traditionally sized (i.e. snack sized) wontons. Tsim Chai Kee attracted customers by serving very large portions.

The bowls were packed with noodles and protein. Each broth was different and incredibly flavorful. The noodles were perfectly al dente.

The wontons were the most familiar. The mark of a good wonton is the thinness of the wrapper. A delicate wrapper is more difficult to cook, so it means you really know what you’re doing. Thick wrappers and the mark of an amateur. That bowl had the lightest broth.

The beef brisket’s broth was more savory and had a bit more umami flavor from the beef fat. The way the meat was cut is a bit different than what you get in the states if you order brisket. This was thinly shaved pieces of beef that didn’t fall apart.

The fish balls were the most foreign to us. The best way to describe the balls themselves is like a cross between a fish sausage and a fish meatball. Dace is ground up and mixed with herbs. They’re shaped into amorphous blobs and cooked (I presume in the broth), which was salty and herbaceous.

Yvonne also ordered us a side of steamed bok choi with oyster sauce. It was very delicately cooked and quite refreshing.

I enjoyed sampling each dish. In the US, we would have tried a few bites of each but left most behind to save room for other food down the road. But it turns out, the downfall of a food tour in China or Hong Kong is that it would be very rude to leave food uneaten. It would be an insult to the chef’s cooking.

So I ate the fish balls, Dad ate the brisket and half of Mom’s noodles, and Mom ate the wontons. And we were stuffed. So it’s a good thing the tour was mostly about culture and history!

There’s no tipping in Hong Kong, so we simply told the owner how delicious the meal was (but since she didn’t speak much English, that mostly meant smiling and nodding a lot).

We rolled ourselves out of the restaurant and ambled uphill. We passed a Chinese herb shop and saw someone wrapping custom blends of medicinal brews in brown paper packaging.

We turned off the main drag and passed a couple of dai pai dong (street food stalls). These used to be incredibly common in Hong Kong but are now endangered. The government didn’t think they looked modern enough and it was difficult to enforce health codes, so they passed a law that said you could only transfer the license to a blood relative. That meant if your son or daughter didn’t want to continue the family tradition, the stall died out. There are fewer than 20 food stalls left in Hong Kong. They used to be exclusively patronized by old people, but now that they’re in danger of disappearing completely, there’s renewed interest from the younger generation.

One stall we passed serves breakfast sandwiches made of shredded cabbage, peanut butter, and condensed milk. Dad and I would totally have tried it if we weren’t so stuffed and there were any tables available.

Yvonne had some interesting insights about the health and safety of the street food stalls. She said if you see locals eating at them you know they’re safe (and probably delicious) because these people are feeding their friends and neighbors. If they poisoned anybody they’d be out of business! Also, everything is bought fresh daily and cooked to order, so nothing sits around spoiling.

To emphasize her point, we turned the corner and were suddenly in the middle of Graham Street Market, one of the few remaining wet markets in Hong Kong (named that because their streets are often very wet). These markets are a mishmash of vendors selling fresh fruits, tofu, eggs, and other ingredients. Some things we recognized, others we didn’t at all.

The market was a colorful jumble or organized chaos. The patrons were mostly locals. Yvonne told us this market was more tourist/camera-friendly than some others because they’re currently fighting to remain open. That said, we were obviously tourists, and the atmosphere wasn’t exactly welcoming, more neutral. I suspect the locals felt about me the same way I feel about tourists when I’m trying to carry groceries on Michigan Avenue (“You may make the economy go round, but for the love of God don’t stop in the middle of the sidewalk to gawk!”).

Mom had a brief run-in with a cantankerous old lady when she tried to tie her shoe on the edge of her stall. In fairness, it was pretty decrepit and didn’t look like it was occupied.

Bamboo-scaffolding sprouted around construction sights all along the street market. That’s one of the reasons they’re fighting to stay open. Much of that area is being torn down and replaced with high-rises, threatening to push them out. So far, they’ve dug in their heels and the local community seems to be supporting them.

The bamboo scaffolding is strong but bends in the wind (unlike steel) so it’s good for typhoon season

At the top of the market, we turned to the right and walked along the meat and fish stalls. Each stall specialized in butchering only one kind of meat. The fish was also incredibly fresh (still flopping around in one case!).

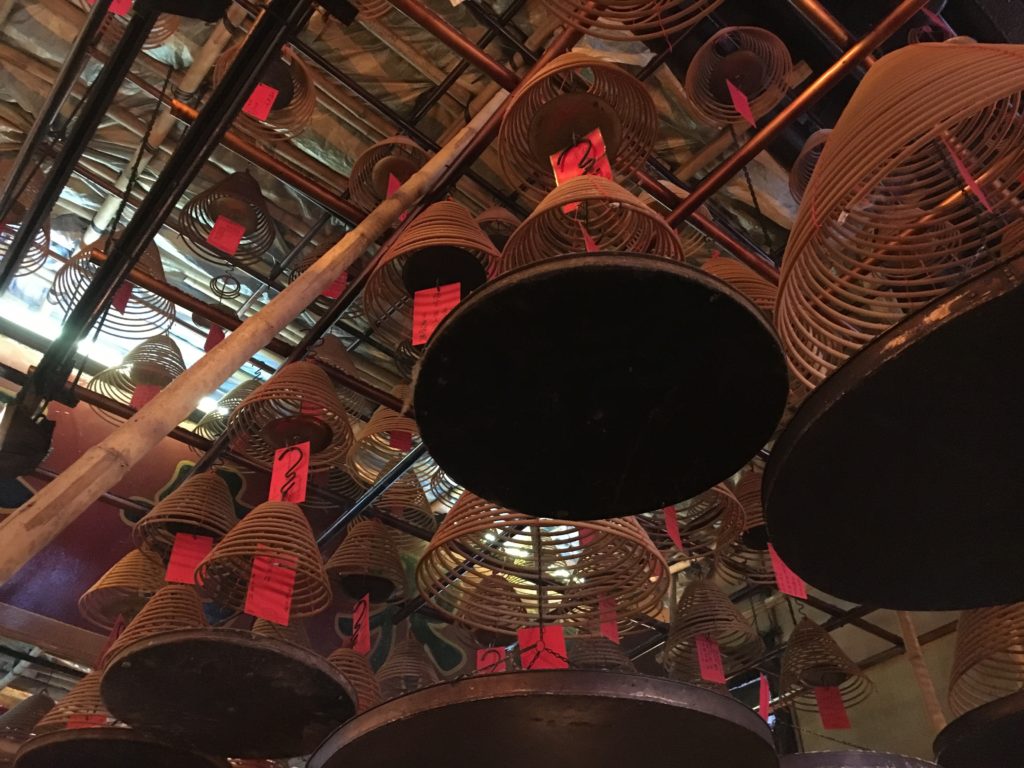

After the markets, we passed a small Taoist shrine tucked in a steep alleyway amidst a jumble of residences and shops. The incense coils burn slowly with prayers attached. You can also light incense sticks and place them in bowls of sand. These should be done in groups of three, as prayers are sent up to heaven, earth, and humanity.

Yvonne led us through many side streets we never would have found on our own. We passed the historic YMCA. It’s a western-style red brick building, but to make it more inviting to the Chinese the roof tiles were made of green ceramic shaped like bamboo.

We also passed run down or condemned tenement houses, another endangered Hong Kong sight. There’s a very large bias against old things in this city. The tenement style houses are very unpopular with the locals because of their age and lack of elevators. So many have been torn down and replaced with high-rises that there is only one row of livable houses left in all of Hong Kong! A small indie film made a few years ago (actually set in 1940s Kowloon) had to film on this particular street.

One reason these tenements still survive is that until fairly recently this district was a very undesirable location. Hong Kongers are a superstitious lot, and this sector was associated with death because of the plague outbreaks in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Locals feared ghosts and bad luck permeated the region. As a result, only things associated with death ( like coffin shops and antique shops – because antiques are dead people’s former possessions) populated the area. And the only people who lived there were poor. That history is slowly being forgotten and the neighborhood is in the process of being gentrified (hence all the construction). It will be interesting to see what the city is like in 5 or 10 years.

Along the way, we did sample some more food (in smaller sizes). We had chilled sugar cane juice (refreshing but very sweet) and chilled five flowers tea (incredibly delicious and very floral).

We visited a British Candy Shop and then TAI Cheong Bakery, which is famous for their egg tarts. Chris Patten, the last governor of Hong Kong before it was turned over to China in 1997, loved these tarts so much he acquired the rather unflattering nickname of “Fatty Patten.”

The tart was delicious, served warm in a buttery flaky crust with smooth eggy/lemony custard in the center. Ten out of ten would eat again.

Lunch hour is officially 1-2pm in Hong Kong, but restaurant lines become ridiculously long starting about 12:40pm. Since we still hadn’t quite digested all the noodles, we opted to finish out our tour in an air-conditioned English pub (which is actually very Hong Kong, given the colonial influence).

I had a Hong Kong summer beer, Yvonne had a traditional British witbier, Dad had alcoholic ginger beer, and Mom had a virgin Bloody Mary (most importantly, with ice).

Yvonne gave us some recommendations for the rest of our stay. I decided to stick around and explore the area a bit more while Mom and Dad headed back to the hotel via tram.

Yvonne left me with directions to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Science and deposited me onto the outdoor escalators that carry you up from Central to The Mid-levels. The escalators are about one story up, so you have an interesting perspective on the shops and restaurants you’re passing.

I was able to follow her directions right to the museum. The building was very similar to the YMCA in layout and design. Originally it was the Bacteriological Institute, Hong Kong’s first public health laboratory, founded in 1906 because of the plague outbreaks. The governor of Hong Kong pleaded with Britain to send an infectious disease specialist. Eventually they did, and the Institute was founded in 1906.

It was well done and didn’t suffer from Too Many Words (a problem many exhibits have). Possibly this is because every sign had to be in Cantonese and English.

The ground floor had exhibits on the human body, reproduction, and an interesting oral history of the SARS outbreak in 2003. Upstairs had historical displays and a well done video presentation about the plague outbreaks, which lasted almost 30 years (1894-1923). Senior medical students were tasked with dissecting rats to monitor the spread.

After the plague crisis, the Institute continued to test water, dairy products, and other sources to help prevent food poisoning. After the discovery of vaccines, they produced vaccines for several diseases (including smallpox).

Making smallpox vaccines was not very glamorous work. It involved strapping down a calf, shaving its belly, infecting it with cowpox, and then taking samples.

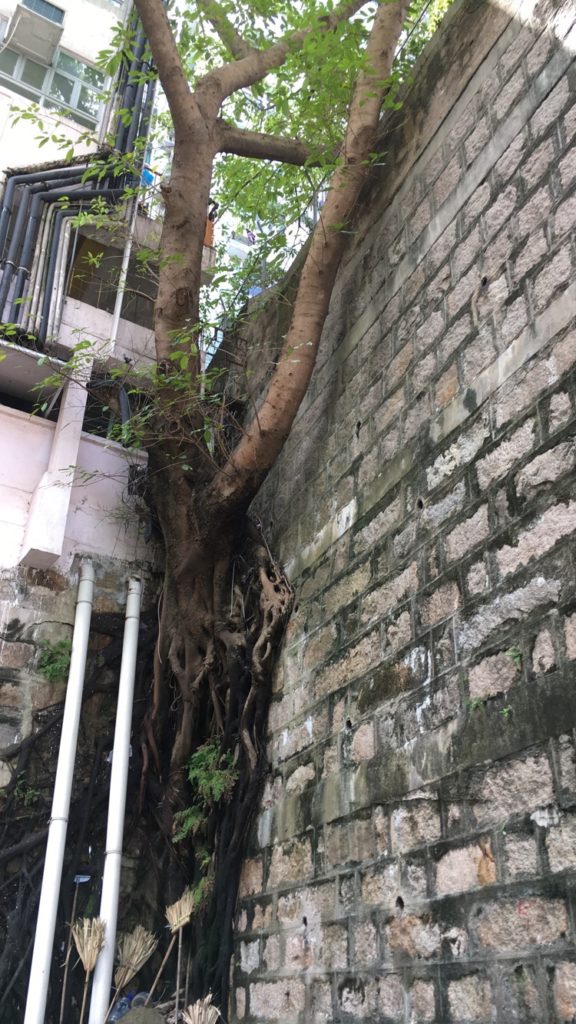

After the museum, I went to Man Mo Temple, dedicated to literature and war. The temple is famous (basically, if you see a movie and there’s a Taoist temple, it’s probably this one). It’s being heavily renovated right now, which made for an interesting experience. The outside is completely covered in bamboo scaffolding but it’s still open to the public. The inside is also being renovated (though not quite as heavily). This means construction workers, tourists, and people praying are all jostling elbows.

After the temple, I headed back to a street we had walked along with Yvonne. I stopped at a local Hong Kong Chain, G.O.D (Gods of Desire), that sells locally made products: clothing, kitchen goods, and souvenirs. Then I started wandering back towards the hotel.

Google maps told me it was only about 1 mile, but I sorely missed Yvonne’s guidance about which streets slope up versus down, where pedestrian over- or under-passes are located, and how to navigate crazy intersections. This city was definitely not designed with pedestrians in mind and it would be a terrible place to be in a wheelchair.

It was a fascinating walk, though. The transition from old Hong Kong, with shabby local establishments, street stalls, and crumbling architecture, is replaced suddenly and sharply with gleaming towers of shiny glass and steel. You’d never guess the other part of the city existed in one place or the other.

There are also lush parks that mask the city. I wandered through one past the Former French Mission Building and St. John’s Cathedral. At the edge of that park, a right turn would have taken me towards Hong Kong Park and the Peak Tram, but a left turn took me towards the hotel (sort of).

It took about an hour, but eventually I wound my way through a maze of streets, overhead walkways, and buildings (blessedly air-conditioned) and found the hotel.

I found both my parents conked out napping.

For dinner, we stayed in the hotel, but sampled the Cantonese restaurant. It’s beautifully decorated and had mirrors everywhere (including the ceiling).

We didn’t have a reservation, so we ended up at a giant table with a large Lazy Susan. That actually made it very easy to share dishes.

The menu offered half portions, which were perfectly sized for us to sample several dishes. I don’t think I’ve ever been someplace where the portions were larger than America before!

We had a bbq meat sampler (with honey bbq pork and crispy chicken skin), prawns with chili roe sauce, tilefish and pea sprouts, crispy chicken, asparagus, and wagyu foie gras fried rice. Everything was very tasty (even Dad liked most things). We also had a fantastic bottle of wine, a 2010 Clos de Vougeot de la Vougeraie that Dad was extremely pleased with.

After such a full (and hot) day, I crashed as soon as we got back to the room.

Check out the day’s snap story here: https://youtu.be/05oBiEF-g18

And here are some more miscellaneous pictures: